While studying Plato, I felt an intuitive resonance between his Theory of Forms (प्रत्ययवाद) and the non-dual insights of the Upanishads. Though his theory was critically examined by later philosophers, including his own student Aristotle; the deeper intention behind Plato’s Ideas seems to reflect a search for an ultimate, unchanging Reality behind the flux of appearances.

This quest is strikingly parallel to the Upanishadic vision of non-duality (Advaita), particularly in the Mandukya Upanishad, where the expression “एकात्म्यप्रत्ययसारम्” (ekātmyapratyayasāram) suggests that the essence of consciousness is the awareness of oneness. Plato’s “Idea of the Good” or the realm of Forms appears, in a comparative framework, as an intellectual ascent toward that same indivisible essence.

Moving further back in Greek philosophy, when we encounter Parmenides of Elea (5th century BCE), the parallels deepen. His concept of “Being” as singular, ungenerated, eternal, and unchanging echoes profoundly with Advaita Vedanta’s Brahman. Parmenides’ assertion that “Being is” and “Non-being is not” resembles the experiential affirmation of सोऽहमस्मि (Sohamasmi — “I am That”).

(Photo Courtesy : Linda Hall Library)

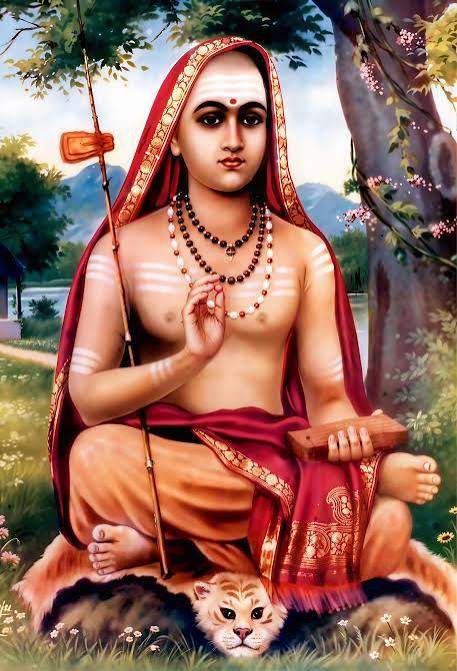

In that sense, metaphorically and philosophically, Parmenides may be viewed as a kind of “Acharya Shankara of Ancient Greece,” though not in competition but in spirit. The non-dual substratum of Reality seems to surface independently across civilizations. Interestingly, some traditional calculations associated with Adi Shankaracharya (as per Govardhan Matha and other Matha traditions) place his timeline much earlier than commonly accepted academic dates, roughly in proximity to the 5th century BCE creating an intriguing comparative horizon.

Even the inscription at the Temple of Delphi — associated with Temple of Apollo, bears the famous maxim “Know Thyself.” In certain interpretative traditions, related aphoristic expressions like “Thou Art” resonate deeply with the Upanishadic mahāvākya तत्त्वमसि (Tat Tvam Asi — “Thou Art That”). The philosophical impulse here is identical: to turn awareness inward and discover the identity between the individual self and the ultimate Reality.

However, this reflection is not meant to compare civilizations competitively, nor to claim influence in a simplistic historical sense. Rather, it highlights the universality of philosophical intuition. When wisdom matures, it often converges.

The very word philosophy, attributed to Pythagoras, means “love of wisdom.” In the Indian tradition, this corresponds to Darśana, not merely a system of thought, but a vision, a direct seeing. If one is truly a lover of wisdom, there is no rivalry, only refinement, expansion, and dialogue across perspectives.

All “isms”- Idealism, Realism, Monism, Dualism – are but conceptual articulations within the larger umbrella of Philosophy. They are lenses, not boundaries. From an inclusive standpoint, the essence remains One, though expressions differ.

Thus, whether we approach Reality through Plato’s Forms, Parmenides’ Being, or the Mandukya’s ekātmyapratyayasāram, the movement is toward unity. The languages differ. The metaphors differ. But the aspiration to know – That by which everything is known – remains shared.

In this core essence, philosophy is not division, but convergence. Not competition, but communion. Not fragmentation, but inclusion.

And perhaps that is the truest spirit of both Philosophia and Darśana.